Women’s Reservation System in Bangladesh: A Review of On Ground Policy

Bangladesh gained independence in 1971 and adopted a parliamentary form of government soon after independence wherein the President was the head of the State, and the Prime Minister was the head of the government, a system similar to India. Bangladesh invoked its fourth constitutional amendment in 1975, placing the President to take over as the head of the government to tackle the tumultuous state of the economy and mounting fear of underdevelopment and unemployment. Many believe Mujib Sheikh did so to retain absolute power, followed by the nationalisation of media that was critical of his actions and shutting down several newspapers across Bangladesh.

However, Sheikh could not enjoy absolute power for long as soon, a coup led by President Mujib Sheikh’s Commerce Minister, Khandaker Mushtaque Ahmed, with the help of the military-led assassination of Sheikh and the establishment of an Islamic government replaced the secular government of Sheikh. The trend continued till 1991 when a popular uprising dethroned Military dictator General Ershad and established a parliamentary form of government. Since then, Bangladesh has been a parliamentary democracy with a two-tier administration at the national level in order.

The central secretariat is at tier one at the national level and harbours various ministries, each headed by a political leader/minister appointed by the President. While the political head of a ministry is a minister, the executive head is the secretary or an additional secretary in the absence of a secretary. The secretary oversees various divisions and advises the minister on policy matters. Each division is further divided into various wings, each headed by a joint secretary. Each wing further diverges into branches, headed by a deputy secretary. Branches are further segregated into sections, headed by additional secretaries.

The Field Administration, or the branch of the Central government that deals with the implementation of policies on the ground level, forms the second tier of the government. The field administration is divided into divisions, districts, and Upazilas to facilitate administration function and easy implementation of policies. The main function of a division is to coordinate various activities at the district level and hear appeals on the decision of district revenue collectors on matters of revenue collection (Panday, 2019; Ahmed, 1986). There are a total of eight divisions in Bangladesh.

Further, below the division level exists the district level that deals with issues of state administration such as law and order situation, collecting land revenue, maintenance of state resources, etc. Currently, 64 districts in Bangladesh also serve as the administrative seat. Below districts lie Upazilas which is the lowest tier in field administration. The Upazilas perform functions similar to Districts such that they collect and maintain revenue, and look into matters of general administration, magistracy, et al.

The local administration in Bangladesh forms the basis of the citizen-centric democratic approach. Article 59 of the 1972 Bangladesh Constitution calls for “local government in every administrative unit of the Republic shall be entrusted to bodies composed of persons elected in accordance with the law.” (Panday, 2019) Currently, Bangladesh follows a three-tier administration in local governance. It consists of Zila Parishads at the topmost tier, Upazila Parishads at the secondary level, and Union Parishads at the lowest tier, which are similar to the gram panchayats of India. Similarly, the urban administration is divided into city corporations and municipalities such as New Delhi Municipal Corporation in New Delhi Constituency of the capital region in India.

However, there are loopholes in defining the relationship between the central administration and the local administration. Over the years, this relationship has evolved and moved towards more clarity. The central administration handles issues of regular administration while local area development lies in the hands of the local government. Even then, the local government has to depend upon the central government officers for the approval of these projects while they can not have a say in the ground-level initiatives of the central government.

Women in Bangladesh Administration

Some of the key points in the discussion around Bangladesh’s administrative system include discussions on Bangladesh being one of the fastest-growing economies of the world, the measure of e-governance in the 21st century, women in administration, etc. Bangladesh since 1991 constitutional reforms have tried to address most of these issues. In Bangladesh, women in the administration were significantly lower historically as compared to the large part of the world. According to a report on Women as Parliamentarians, Rwanda led the world in 2003 with 48.8 percent women in its national Parliament, followed by Sweden with 45.3 per cent in 2002 and Norway with 38.2 per cent in 2001. Currently, as of December 2022, Rwanda leads with 61.3% women in parliament followed by Cuba at 53.4, and Nicaragua at 51.7%. In 2001, Bangladesh was far down the global rankings in 122nd place with 2.0 percent of women in its national Parliament.

However, more recent figures tell a better story. As of January 1 2019, Bangladesh holds a global rank of 95, with 72 female parliamentarians (20.7 per cent) out of 350 (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2019) (Ara 2020) and 20.86% women in parliament in 2021. Though the situation has improved, there is still a lot to be done in closing in on the gender gap in administration. Politics and administrative structures are mostly male-dominated in most parts of the world. This is due to the inherent patriarchy where women are not allowed to hold high offices or cease to consolidate victories in their favour.

The United States of America has not found a woman heir to the top office of President in its almost 247 years of independence; the United Kingdom voted for Margaret Thatcher in 1979 as the first female Prime Minister; even though Thatcher had to leave the office after a trailblazing record of 11 years of the premiership, many believe that her removal from the office was due to intolerance of the male leaders of her party. Even while staying in office, Thatcher did not do enough for increasing the direct participation of women in politics/parliament, appointing only one female cabinet minister in 11 years. “Far from ‘smashing the glass ceiling,’ she was the aberration, the one who got through and then pulled the ladder up right after her,” The Guardian columnist Hadley Freeman wrote after Thatcher’s death at age 87.

While the U.S. and the U.K. have struggled to find women leaders in the topmost offices who have led an exemplary battle for women on the ground, South Asia stands as an exception. It is Indira Gandhi of India and Benazir Bhutto of Pakistan, along with Khalida Zia and Sheikh Hasina of Bangladesh, who have defined administrative structures and women-led governments of their respective countries in a significant manner. “Women must negotiate various contested spaces and arenas when entering politics or being actively involved in this domain. In the specific conditions of Bangladesh, various restraining societal attitudes related to traditional discourses of femininity, reinforced by religious ideas and norms,” writes Ara (2020). The socio-cultural factors such as raising funds for contesting and campaigning in the elections, not being taken seriously, networking, and lack of safety while travelling to various parts are some reasons that restrict a woman’s entry into the political field, especially in Bangladesh along with the patriarchal patterns in which the society functions.

Women have a hard time convincing voters that they can be the ideal representative due to the internalised patriarchy that makes politics a male-dominated sphere. Similarly, the voting trends in Bangladesh reflect a low percentage of women voters, with men influencing the overall decisions of women. Researchers and political analysts suggest that the low participation of women in politics is also due to a lack of knowledge among women about their rights:

There is a lack of awareness among Bangladeshi women about their legal rights recognised nationally and internationally. Besides, the patriarchal and patrilineal social systems, traditional values and norms and shortage of full-time activists are barriers to greater participation of Bangladeshi women in the political process to have a share of the political pudding – their proper representation in the political bodies, in the decision-making arena and bargaining power in [the] community. These barriers to greater participation, along with lack of consciousness, have resulted in their failure to be organised and thereby eventually perpetuated their subordination and disempowerment. (Hossain 1999)

Education certainly plays a key role in boosting the confidence of women and entering the political sphere or any public sphere without hesitation. While the lack of education in women is persistent, Bangladesh has made a steady effort in improving the female literacy rate. Similarly, financial solvency becomes another reason for low female participation as anyone contesting elections needs funds to travel, campaign and engage in several other activities. Party funding is not always available, and candidates have to manage through donations and private wealth.

Another significant reason for low female participation is the responsibility of the family. With the increase in nuclear families, women have fewer support options to cater to their family responsibility while they are at work. This lack of family support options and family responsibilities leads to women refraining from active politics. As in other fields, women have to face sexual harassment, including political violence in this sphere. Travelling long distances for campaigning also becomes a safety concern. According to a report by the International Foundation of Electoral Systems in 2017, a few ways practised by patriarchy to deter women’s participation in politics are:

- Women’s political participation in Bangladesh is hampered by pervasive violence that happens in the political field. Women have to often deal with political attacks and clashes. This further leads to reduced support from their families, limiting their political participation.

- Further, women receive more psychological violence such as sexist remarks, indecent commentary, intimidation, harassment, etc. Similarly, women have to deal with psychological abuse at home for remaining away from home for long hours.

- Many female candidates have been sexually harassed and molested in political campaigns and rallies. Sexual violence in the form of harassment and assault of women candidates, political activists and voters.

- Lack of financial support from the parties or withholding the funds further deter women’s political participation.

Women Reservation Bill

Even though the participation of women in politics is limited due to the aforementioned factors, Bangladesh has tried to increase participation legally and constitutionally. While women continue to fight cultural and social factors, the policy framework has tried to safeguard their interests. Bangladesh introduced the reservation for women in the National Parliament in 1972 with their first constitution reserving 15 seats for 10 years in addition to the existing 300 seats. Then in 1979, these seats were increased to 30, taking the total parliamentary seats to 330 for a period of the next 15 years.

When the amendment expired in 1987, no seats were left reserved in the subsequent general elections. Introducing the 10th amendment to the constitution in 1990, again, 30 seats were reserved for 10 years till 2000. In the 2001 general election, no seats were reserved. However, the 14th amendment to the constitution guaranteed 45 seats to women for 10 years. In 2011, passing the 15th amendment to the constitution, Bangladesh reserved 50 seats for women, taking the total tally of the National Parliament to 350 seats. The current Parliament elected 72 female members that are 20.7% of the total Parliament which as of 2021 stands at 20.87%.

However, analysts believe that this can not be counted as a real change since 50 out of these 72 seats were already reserved for women, electing only 22 women out of the other 300 seats. Similarly, 25% of the seats are reserved at the local level for women which has resulted in increased participation even though these regions are largely male-dominated and women leaders have to fight their way every day in order to govern and fulfil their responsibility.

Union Parishads, which are the building blocks of the local governments, are further segregated into nine wards, each with three wards, that is, 33% of wards are reserved for women. Women elected from reserved seats experience challenges that are far different from those elected from general seats. Women selected from general seats have to face cultural and societal challenges. However, the ones elected from the reserved seats face cultural and social challenges along with systemic challenges. For meaningful representation, women need to contest from general seats rather than being selected for the Parliament via reserved seats. According to a 2013 survey by the Khan Foundation,

65 percent of respondents indicated that women must contest general seats in order to achieve ‘political empowerment.’ This is in contrast to the only 25 percent of respondents who indicated that a greater number of reserved seats would achieve the same goal. Also, only 54 percent of respondents were of the opinion that reserved seat members in Parliament have ‘played some role’ in politics. The people that responded in the negative gave the following reasons: political parties not taking reserved seat holders seriously (50%) and ‘absence of proper allocation of work area’ (42%).

However, a rampant criticism of this reserved seat structure has been that the nomination for these seats has not been transparent. “Since the reserved seats in Parliament are not elected and are instead de facto selected (general seat M.P.s technically comprise the electorate, but the reserved seats have never actually gone to vote).” (Mcdermott 2015) This results in parties placing the people randomly on the list as per their choice offering no real opportunity to those who are more qualified by merit.

The charges of nepotism on incumbent governments have been common in this regard. Furthermore, parties need not elect members from different geographical regions or different socio-economic backgrounds in order to maintain diversity. Lastly, women selected for these seats are considered to be less legitimate than those elected from general seats. Similarly, there is tokenism in this appointment as questions asked by these members are not considered important, nor is there representation in the cabinet.

Lessons for India

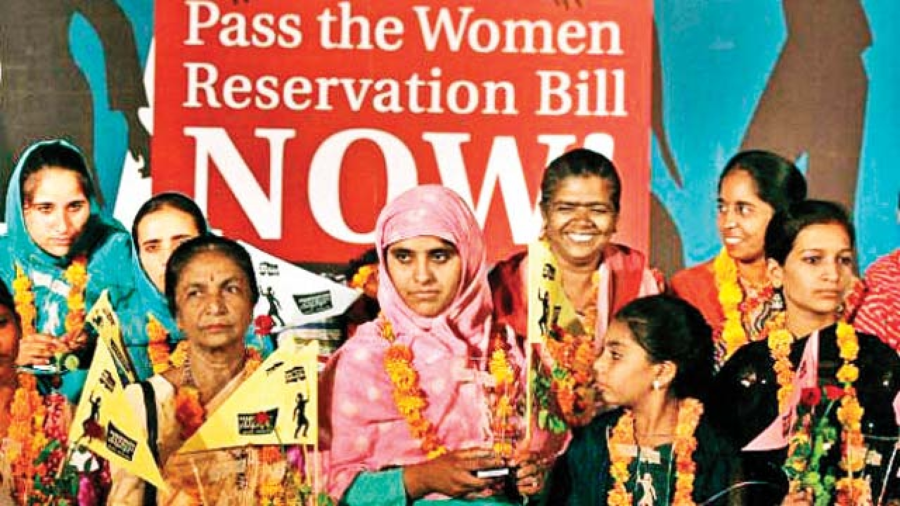

Even though there are still structural issues with the reservation system of Bangladesh, it offers valuable lessons from its experience to South Asian counterparts such as India. There has been a constant demand in India from various sections of the societies to implement a 33% reservation for women in Parliament. The Women’s Reservation Bill 2008, which enables one-third of seats in the lower house of the country as well as the state legislative assemblies to be reserved for women on a rotational basis, was passed by the upper house which is the Rajya Sabha on March 9, 2010. However, for a bill to become a law in the country, it needs to be passed by both houses and further sanctioned by the President of the nation. Despite being cleared by the Rajya Sabha, the bill never made its passage to the Lok Sabha. India ranks 20th below in terms of women in Parliament. The 2019 Lok Sabha saw the highest number of females to be elected to the lower house. Seventy-eight women were elected out of the total 545 seats, which account for almost 14%, way less than Bangladesh’s 21%. The Women in Reservation Bill needs to be passed in Parliament in order to ensure a higher representation of women in the electoral process. This will further ensure the passage of bills that can empower women in various fields, rising above tokenism and representation only in the name.

Conclusion

Political Representation is integral to bringing structural changes in the way society is governed. Opportunities for women in politics promote gender equality and make way for a more just and equal society based on policies and practices that cater to the needs of underprivileged women. Women add diversity to opinions in the existing societal setups which are otherwise exclusively patriarchal. While there is sufficient evidence that more women in politics pave way for women-friendly legislation, there is not much evidence to show the impact of politicians’ gender on the economic performance of the country. However, several initiatives such as Bangladesh’s Women Entrepreneurship Development Unit (WEDU) enhanced the participation of women entrepreneurs in the economy by providing easy access to credit and funds. Therefore, there is immense significance of women in the political sphere around the world to enable and promote an inclusive and just society.

References

- Administrative Structure of Bangladesh 2018. https://www.slideshare.net/fahim002/administrative-structure-of-bangladesh

- Ahmed, K.U. (2008) ‘Women and Politics in Bangladesh’. In K. Iwanaga (Ed.), Women’s Political Participation and Representation in Asia: Obstacles and Challenges (pp. 276–96). Copenhagen: NIAS – Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

- Ara, F., & Northcote, J. (2020). Women’s Participation in Bangladesh Politics, The Gender Wall and Quotas. South Asia Research, 026272802091556. doi:10.1177/0262728020915562 https://sci-hub.se/https://doi.org/10.1177/0262728020915562

- Chowdhury, F.D. (2009, September) ‘Problems of Women’s Participation in Bangladesh Politics’, The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs, 98 (404): 555–67.

- Chowdhury, N. (1994) ‘Bangladesh: Gender Issues and Politics in a Patriarchy’. In Barbara. J. Nelson & N. Chowdhury (Eds), Women and Politics Worldwide (pp. 94–113). New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Hossain, M.A. (2012) ‘Influence of Social Norms and Values of Rural Bangladesh on Women’s Participation in the Union Parishad’, Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 19 (3): 393–412.

- Hossain, M.Z. (1999) ‘Strategies for Empowering the Women in Bangladesh’, The Chittagong University Journal of Law, 4: 62–88

- International Foundation for Electoral Systems. Effects of Violence on Women’s Participation in Bangladesh. 2017 https://www.ifes.org/sites/default/files/2017_ifes_effect_of_violence_on_women_participation_in_bangladesh.pdf

- Mohalla, A H. Growth and Development of Civil Services in Bangladesh- An Overview of South Asian Survey. The University of Rajshahi. Vol 18. 2019 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283005239_Growth_and_Development_of_Civil_Service_and_Bureaucracy_in_Bangladesh_An_Overview_South_Asian_Survey_Vol_18_No1137-156/link/5acc6f44aca272abdc64c977/download

- Panday, P.K. The Administrative System in Bangladesh: Reform Initiatives with Failed Outcomes. University of Rajshahi. 2020 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325997908_The_Administrative_System_in_Bangladesh_Reform_Initiatives_with_Failed_Outcomes/link/5c7e1008458515831f83edb2/download

- Panday, P.K. (2008) ‘Representation without Participation: Quotas for Women in Bangladesh’, International Political Science Review, 29 (4): 489–512.

- Khan, S.Z. (2018) The Politics and Law of Democratic Transition. Caretaker Government in Bangladesh. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Schuster, Christian. Civil Services Management in Bangladesh. University of London. London. 2019. http://christianschuster.net/2019.03.10.%20Bangladesh%20FOR%20PUBLICATION.pdf

- Zaman, F. (2012) ‘Bangladeshi Women’s Political Empowerment in Urban Local Governance’, South Asia Research, 32 (2): 81–102.