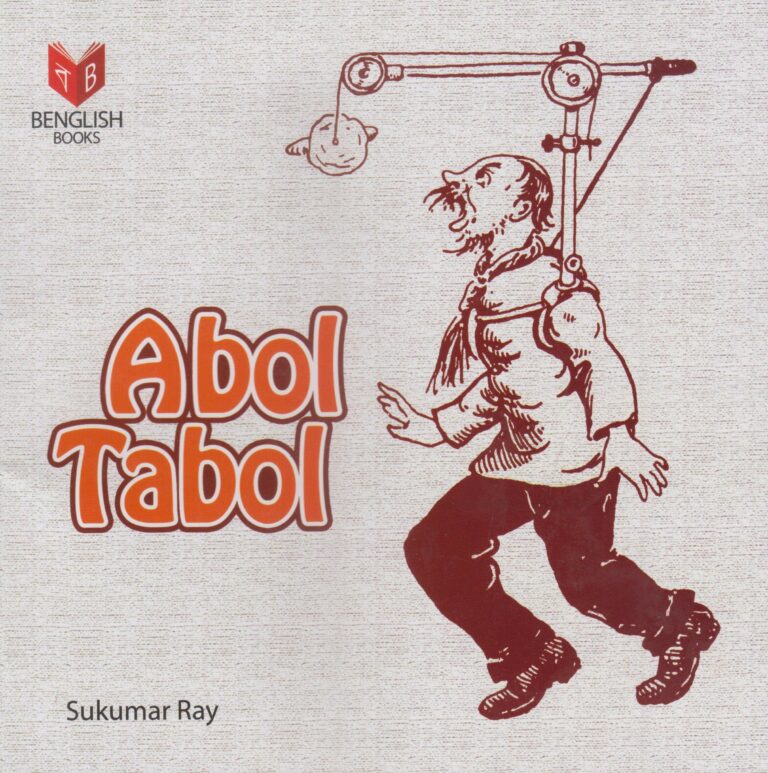

The political sense behind the non sense: Deciphering Abol Tabol

Sukumar Ray was India’s first poet to use illustrations as an important part of his work. Far from being relegated to a secondary position, his illustrations significantly change, subvert, and enhance the ‘representational idioms’ of the nonsense verse. The illustrations depicting invented beasts, comprising original sketches by the author himself, are an essential part of the literary nonsense texts in Abol Tabol. Ray, a British colonial subject, exemplifies Bhabha’s notion of an ‘empowered hybridity’, unsettling ‘problematic binarism’ with respect to identity formation. Ray’s imaginary animals resisted classification as a single discernible species and are fantastic amalgamations, instead.

His exploration of hybridity is imbued with a ‘form of ambivalence’ that acknowledges both the ‘progressive potential’ as well as the ‘undesirable aspects’ of hybrid forms of existence. Hence Ray did not even spare those ‘mimic men’ from his community, who represented, in terms of socio-cultural cross-pollinations, the insidious effects of unequal power relations within colonial society. This is exemplified through Ray’s extensive use of the hybrid form of Bengali literary nonsense, where a western genre is brought together in a new harmonious blend with the existing indigenous literary heritage within his overall body of work. Equally important are the varying representations of hybridity in his nonsense texts, for instance: the monstrous and absurd animals and situations his verses and accompanying illustrations delineate. (Bhadury, 2013)

Ray, The Political Cartoonist

Khichudi (Hotch-Potch), the first nonsense verse in the collection, signals the anthology’s whimsical nature, presenting a medley of improbable beasts that adequately portray Ray’s ambivalence toward the notion of hybridity. The poem includes several portmanteau animals in light-hearted rhymed couplets that aim to amuse and delight its readers. Even in this jolly nonsense verse, there exists a range of motivations, emotions and reactions to different animals melding together to create fantastic new crossbreeds. The desire on each count is different and so are the results and effects.

Ray’s portmanteau illustrations in Khichudi are significant because they demonstrate his unease with an unequal power balance that is almost always weighed heavily in favour of one dominant species. The question of shrinking and enlarging to accommodate vast differences in size implies that the animals do not undergo equal transformations. Rather, Ray points out that when it comes to (colonial) cultural hybridity, there is no ‘ideal mix’. In the case of hybrid identities, some aspects of competing cultural influences need to flare up and others need to be diminished or even obliterated for the fusion to work. His illustrations in this instance present a visual critique of the politics of forced and/or unthinking cultural fusion with one dominant culture gaining undue prominence or control over the other.

The verse only informs readers of the creatures that are being combined. It does not give them any hints as to how the combination takes place, or the order in which it does so. The illustrations mend this gap in the readers’ knowledge by iconographic signs that represent the final composite animal, and in the process, also lay bare the question of power hierarchies. If the different elements of these hybrid animals represent varying cultural influences, the final results of the combinations subtly indicate who has greater control over the new discourses formed by forced or otherwise cultural enmeshing.

In the combined animals, the one that has its head intact is likely the one in charge, as it were. At the very least it is the one able to articulate aspects of its new state of being. Ray’s illustrations are instrumental in understanding such satiric commentary. In the case of Khichudi, Ray arguably makes more of a political statement through his illustrations than he does through his verse. The illustrations lend new significance and meaning to the text, which might otherwise merely have been amusing and nonsensical on its own, by subtly pointing out the delights as well as the dangers in (unchecked) cultural assimilation. (Bhadury, 2013)

In poems like Kimbhut (Superbeast) and Tyansh Goru (The Blighty Cow), on the contrary, pointed anti-colonial satire replaces gentle irony while representing the topic of hybridity, highlighting its negative aspects in a far more strident manner. Ray is no longer ambivalent about those members of contemporary Indian society who eagerly abandon their own identities in favour of an unthinking (foreign) cultural amalgamation, and the illustrations play a vital role in representing the anxieties attendant upon these mixed creatures.

In Kimbhut (Super-beast), Ray directs his critique toward the enmeshing of varied traditions without proper contextualization. The titular beast, utterly dissatisfied with its appearance and attributes, desires specific attractive features from a host of different animals: an elephant’s trunk and tusks, a bird’s wings, a songbird’s sweet voice, a kangaroo’s legs, a lion’s mane and a lizard’s tail. When its wish is miraculously granted one day, the untenability of this new hybrid existence rapidly sinks in. Kimbhut morphs into a cautionary tale, representing an instance of hybridity gone awry. The black-and-white sketch accompanying Kimbhut stretches to an extreme the problems of scale and proportion of the different animal parts and the question of competing power hierarchies addressed by the illustrations in Khichudi. The illustration depicts the Kimbhut standing alone, shoulders stooped, depicting a picture of misery. In this instance, through both verse and illustration, Ray presents a creature so far out of the realm of desirability that it serves both as a target for mockery and as well as a warning to those who would follow the super beast’s example and crave perceived attractive qualities of different cultures and societies without regard to the consequences. The Kimbhut now fears being called a ‘proper disgrace’ and so he sadly cries out-

“Oh what can I be?”

The generalised satire of Kimbhut morphs into a pointed critique of colonial enthusiasts in Tynash Goru (The Blighty Cow), especially of the ‘brown sahibs’ who imitate western customs in misguided ways. The tynash goru’s carefully westernised grooming, delicate and fussy demeanour and absurd diet paint a mocking portrait of the subservient native subject of British masters. Ray ridicules the Indians who were all too eager in their unthinking imitation of different aspects of British society and culture.

As Sampurna Chatterjee points out, “even today when you use the word ‘tyansh’ for someone, it is derogatory and means overly and unpleasantly westernised.” (Bhadury, 2013) The illustration of this poem emphasises Ray’s message to an even greater degree. For instance, it depicts the tynash goru’s eyes as closed, presumably to the reality of the world outside. The creature rests in typical bovine complacency, sprawled in a slack, ungraceful manner, chewing (one imagines) the tallow candles placed next to it. The specific choice of a cow, generally regarded as a domesticated, passive beast that does not show any initiative or intelligence of its own and is raised only to serve humans, is a significant one. It allows Ray to pictorially portray to an even greater degree the tynash goru’s unthinking meekness, which within a British colonial context, becomes a dangerous form of compliance to an oppressive and unjust foreign authority.

The illustrations of Ray to verse works like Allhadi, Kaduney and Haturey show a caustic parody of British culture. The illustration of Ekushey Ain is equally significant for the arbitrariness of British misrule and also noticeable. Khuror Kol, Gnof Churi and others show a more westernised ‘babu’ culture and indulge in its parody.

Thus, Sukumar Ray’s creative output needs to be considered in the context of a literary and cultural milieu, one that was a product of complex, hybrid socio-cultural and political forces. His nonsense poetry and illustrations, therefore, encompass a complex mixture of the East and the West and a medley of diverse discernible influences, as well as works of unprecedented originality. He exemplifies Bhabha’s notion of an empowered ‘hybridity’ where one unsettles ‘problematic binarisms’ with respect to identity formation and lays claim to several different cultural influences with equal ease.

Ray’s own persistent explorations and representations of the issue of hybridity are complex and ambiguous, embracing both positive and negative connotations of such amalgamated social and identity formations. His Tyansh Goru (The Blighty Cow) metaphorically represents, and hence satirises, the subservient Indian clerks produced by the British colonial machinery. While applauding the positive aspects of simultaneous exposure to diverse cultures, Ray criticises the severe oppression and inequalities that colonialism perpetuated. (Bhadury, 2013)

In Ray’s case, indigenized literary nonsense becomes a ‘counter-discursive practice’, and a vehicle of contemporary political and social commentary, primarily via a satiric critique of the British colonial government and their repressive policies, along with certain Indian institutions and personages, like the overly westernised babu in Tynash Goru or the complex beast in Kimbhut. It is highly important to emphasise the fact that although meant primarily for children, and containing a strong ‘humorous and whimsical strain’, Ray’s nonsense is highly political. Ray often used his literary nonsense as satire, commenting obliquely on the colonial society and British administration of the day. For Ray, a colonial subject, the question of competing cultural influences is especially crucial and this is reflected in his choice of literary genres. In fact, as Sumanyu Satpathy expounds, “that which we call modern or literary nonsense in India is a hybrid product that arose from colonial contact.” (Bhadury, 2013)

In Abol Tabol the magical met the real in brilliantly matched words and images but these nonsense poems specialised in Bengali idiosyncrasies. Their ‘untranslatability’ stems from the fact that the puns and alliterations ingeniously juxtapose Bengali and English. Sukumar Ray plays with the Bengali resonance of certain English words and images inextricably bound to bhadralok/babu culture. This mixture made perfect sense in the bilingual colonial milieu of urban Calcutta in the early decades of this century.

The colonial interaction was prominently a target. The maudlin Tynash Goru was manifestly a hybrid that surely only colonialism could have produced. (Maiti, 2016) Ray’s appropriation of the English literary nonsense tradition in the form of the hybrid Bengali children’s nonsense to such satiric ends, gives his critique a particularly subversive resonance. Here, a political subject uses the literary traditions of the coloniser to mock the latter.

The poems of Abol Tabol are prime examples of the way in which Ray’s subversive, hybridised nonsense functions as a counter-narrative, where both form and content are imbued with a critique of the (western) canon and its exclusion of other narratives (Bhadury, 2013). Few satirists in Bengal rivalled Ray’s vocabulary of invented words and the work that best caught his genius was Abol Tabol. (Maiti, 2016) Thus, Sukumar Ray uniquely blended literary and pictorial wit through his nonsense verses and accompanying illustrations. Abol Tabol is a symbol of his remarkable oeuvre which presents an incisive commentary on hybrid forms of existence and cross-pollinations of cultures in the colonial socio-political milieu of early twentieth-century India.

References

Books

- Ray Sukumar, Abol Tabol, Nirmal Book Agency Sahityam, Kolkata

Journal Articles

- Bhadury, P. (2013) “Fantastic Beasts and How to Sketch Them: The Fabulous Bestiary of Sukumar Ray”, South Asian Review, Vol. 34, No. 1. available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02759527.2013.11932917

- Bhattacharyya, P. (2015, February). “Tracing the ‘Sense’ behind ‘Nonsense”: A comparative study of selected texts of Sukumar Ray and Edward Lear”, International Journal of English Language, Literature and Humanities, Volume II, Issue X. available at: http://ijellh.com/papers/2015/February/53-512-524-February-2015.pdf

- Chakraborty, R. (2014-2015). “Finding Sense Behind Nonsense in Select Poems of Sukumar Ray”, Journal of the Department of English, Vidyasagar University, Volume 2. available at: http://inet.vidyasagar.ac.in:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/1497/1/10.pdf

- Maiti, A. (2016, April) “The nonsense world of Sukumar Roy: the influence of British colonialism on Sukumar Roy’s nonsense poems-with special reference to Abol-Tabol”

Internet Sources

- ______ (2020, August 2). “Nonsense Verse to make a point: Reading Sukumar Ray”, available at: https://buckleyschool.com/magazine/articles/nonsense-verse-to-make-a-point-reading-sukumar-ray