The Child and the Curriculum: Two Ends of the Educational Process

Dr. Jyoti is a professor at Delhi University.

In this essay Professor Jyoti Raina and her student Vaishali Sharma examine John Dewey’s ideas on curriculum and education.

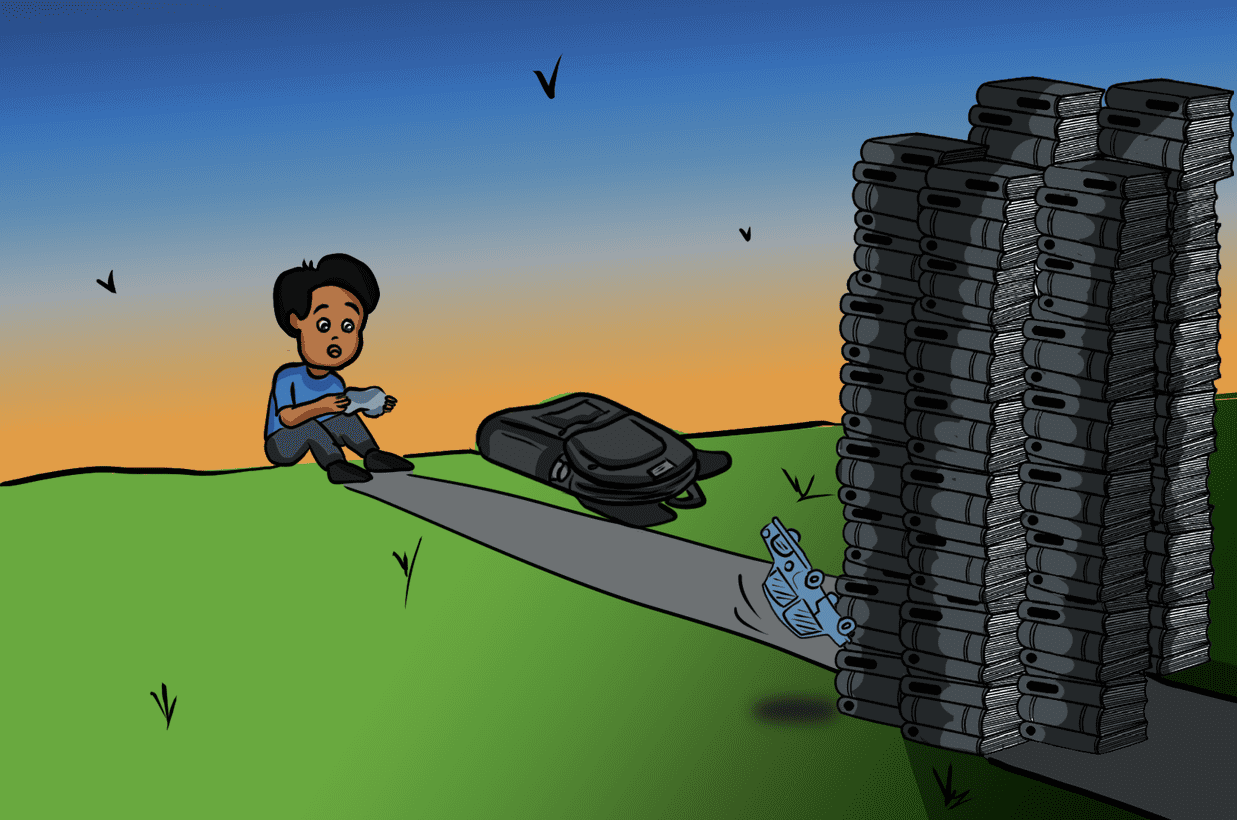

The American philosopher John Dewey (1859-1952) regarded the meaning of the terms ‘child’ and ‘curriculum’ as a major problem in education. He argued that it is a genuine and serious problem since ‘elements, taken at the stand namely the terms-child and curriculum; are conflicting’ (1902:181). He further explains that the two are fundamental but opposing factors in the educative process; the first ‘immature, undeveloped beings’ (Ibid: 182) and the second ‘certain social aims, meanings, values incarnate in the matured experience of the adult’ (Ibid). The separateness, disconnect and opposition in the conceptualisation of the terms child and the curriculum is ‘a really serious practical’ as well as an ‘insoluble, theoretic problem’ (Ibid).

There arises thus the case of the child versus the curriculum; or, of the individual nature versus social culture. The opposition is very visible as ‘the child lives in a somewhat narrow world of personal contacts… his world is a world of persons with their personal interest rather than a realm of facts and laws’ (Ibid: 183). The curriculum, on the other hand, ‘presents material stretching back indefinitely in time and extending outward indefinitely into space’ (Ibid). The child is removed from his immediate life and environment of which he experiences not more than a few kilometre squares in terms of geographical area as well as from the immediacy of memory which in the name of the curriculum is ‘overlaid with the long centuries of the history of all peoples’ (Ibid).

Dewey succinctly highlights three divergences between the child and the curriculum. First that the world of the child is narrow, immediate and personal while the curriculum is impersonal and extends infinitely into both space and time. Second, a child’s life is one of wholehearted unity while the curriculum prides itself on specialisations. Third child nature has psychological attributes like emotional bonds that have practical manifestations in his everyday life while the curriculum is organised on a logical classification based largely on abstract principles. The studies at school, therefore, introduce the child to a world which is arranged ‘on the basis of eternal and general truth’ (Ibid: 186).

Curriculum development involves subdividing these truths into subject studies, or rather specific lessons compartmentalised in the form of various school subjects, or, disciplinary domains and in the final analysis being reduced to particular facts, formulas and principles. Dewey explains the assumption underlying curriculum planning in the words:

“Let the child proceed step by step to master each one of these separate parts, and at last he will have covered the entire ground. The road which looks so long when viewed in its entirety is easily traveled, considered as a series of particular steps. Due emphasis is put on the logical subdivisions and consecutions of the subject matter (Ibid: 186).”

To fill up the child-curriculum schism Dewey proposed a novel conceptualization of the child and the curriculum not as opposing entities but as two limits of the process of education. He writes:

“Abandon the notion of subject matter as something fixed and ready-made in itself, outside the child’s experience, cease thinking of the child’s experience as something hard and fast; see the something fluent, embryonic, vital; and we realize that the child and the curriculum are simply two limits which define a single process. It is continuous reconstruction, moving from the child’s present experience out into that represented by the organized bodies of truth that we call studies (Ibid:189).”

The child-centred movement in education argues that the child is the starting point of the process of education as well as the end. The child is endowed with interests, inherent educability and initiative. The goal of the curriculum is not acquiring a pre-defined body of information or knowledge but self-realization. The growth of the child is the sole purpose of the educational process. In contrast, the main attributes of an opposing conception of curriculum-centred education are discipline, guidance and control. This brings to the fore a distinction between the logical and psychological aspects of the curriculum. Dewey offers an illuminating example of what he means by the logical and the psychological aspects of experience with reference to the curriculum. An explorer of a new country, or geographical terrain writes his or her notes based on ‘blazing a trail and finding his way along as best as he may’ (Ibid: 197).

The finished map that is constructed after the country has been thoroughly explored is a logical construct. The two are mutually dependent. The explorer’s notes can have greater value if they are enriched by similar undertakings of other explorers. The map as a piece of knowledge in geography thus orders psychological aspects of individual experience. It cannot be a substitute for the personal experience but can possibly connect the individual with the experiences of the other. The psychological and logical aspects of learning about the physical surroundings; thus come together to constitute the child and the curriculum as two ends of an educational process.

The field of curriculum studies emerged from Dewey’s writings as a key area of educational studies in his times. He even went as far as to say that all pedagogic opinion emanates from this fundamental antagonism between the child and the curriculum. His essays, books and other writings outline a pedagogic creed which brings social philosophy to school reform through a curriculum based on the immediate life experiences of young children (Dewey, 1902, 1916).

It has been more than a hundred years since Dewey’s re-thinking of the school curriculum. His own attempts at putting his curriculum theory to practice at the Laboratory School of the University of Chicago evinced countless visits from educators from all over the world. The school however had a very short life (1896-1904) and consequently hardly any impact on mainstream curriculum practice. In India, as in most parts of the world, school education has continued to remain disconnected from its psychological aspects, namely the individual experiences of the child. There exists a gap between curriculum theory and practice (Raina & Verma, 2021a, 2021b) as a textbook-centred curriculum views education as the acquisition of an objective body of knowledge eradicating possibilities of children’s learning meaningfully by their own psychological devices (Raina, 2020).

The prevalent practice of a homogenous, standardised examination-driven curriculum falls short of inspiring a child ‘to enter the domain of science and poetry, history and geography, or music and carpentry’ (Pathak, 2022). The textbook culture comes to contemporary school education from our colonial past dominating curriculum, learning and assessment. Re-thinking curriculum practices in schools by envisioning the child and the curriculum as two continuing limits of the educational process lingers as a foundational research-worthy theme. An important concern in curriculum studies in initial teacher education is the development of a research agenda around this major educational problem identified more than a century ago.

References

- Dewey, J. (1902). The child and the curriculum. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York: Macmillan.

- Pathak, A. (2022). ‘Hollowness of exam warriors’, The Indian Express, July 22, 2022.

- Raina, J. and S. Verma. (2021a). A Philosophical Gaze on School Curriculum, The Armchair Journal, April 5, 2021. https://armchairjournal.com/philosophical-gaze-curriculum/

- Raina, J. and S. Verma. (2021b). ‘An Exploratory Study of School Curriculum: Analysing Gaps between Theory and Practice’, Education India: A Quarterly Refereed Journal of Dialogues on Education, Vol.10 (3), 462-473.

- Raina, J. (2020). ‘A Teacher Discovers What is Wrong with Online Teaching in Higher Education?’, Portside: Material of Interest to People on the Left, July 4, 2020.

- Tanner, L.N. (1991). The meaning of curriculum in Dewey’s Laboratory School (1896-1904). Journal of Curriculum Studies, Vol. 23, No.2, 101-117.

Loved how the gap between a child and the curriculum is shown in this article so explicitly. This insightful article impeccably brings out John Dewey’s ideas.

Thank you for the review @Yashika ma’am.

The relationship between the curriculum and the education highlighted by John Dewey is splendidly shown. The article is quite detailed as well as easy to understand.

Very detailed and insightful. I can call it a well written article as the language contains medium level of difficulty and it can majorly be understood by most people. It covers most of the required aspects.

Thanks!