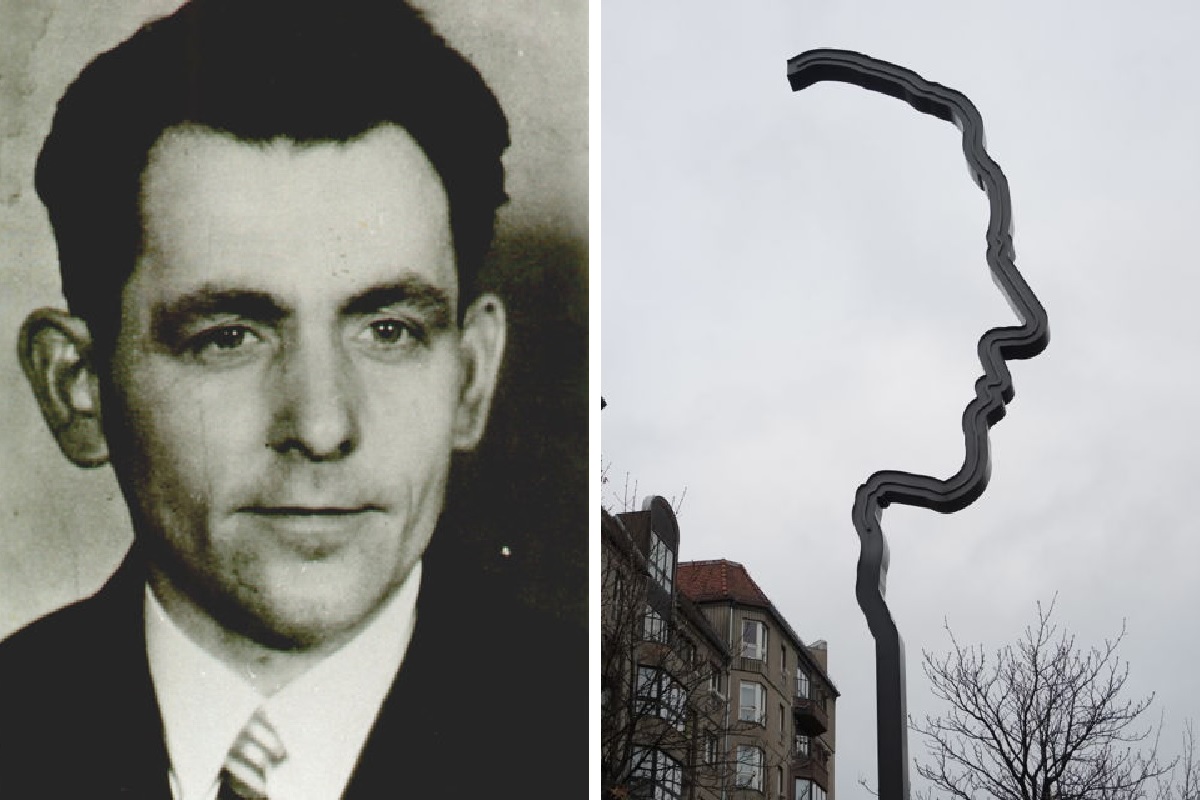

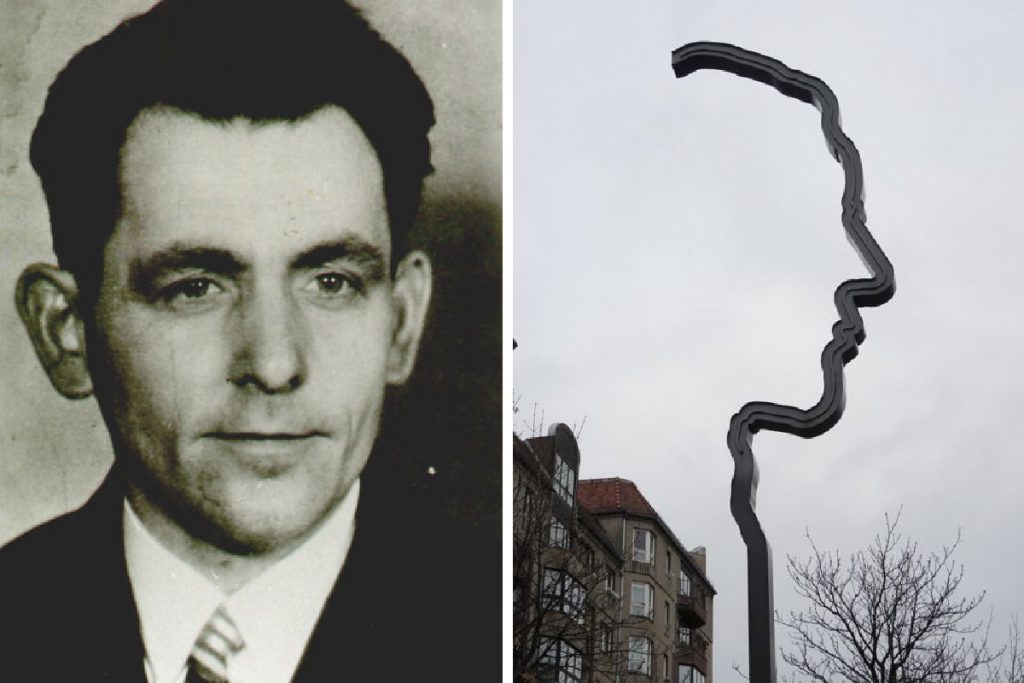

Georg Elser: Remembering a True Antagonist on his 118th Birth Anniversary

Dilip Simeon is a teacher and taught at many universities across India and the world

First published in the Pioneer on Sunday, 7 August 1994

On July 20, The Pioneer published a syndicated article from Hamburg, entitled ‘Hitler escaped assassination by a few inches’. It was written in memory of Colonel von Stauffenburg, the man who carried out the ill-fated bomb attack on Hitler at his eastern headquarters fifty years ago. The aristocratic officer was indeed a brave man, whose actions demonstrated the intense dismay that Hitlerism had caused within the German army. But the statement that his attempt was the “closest anyone in Nazi Germany ever came to assassinating the fanatical dictator” is not true. Stauffenburg is justly remembered, but another German has been erased from the literature of resistance, although his plan came within minutes of saving the world from the horror of the Second World War. It was a plan of the conservative opposition, which became activated only when faced with military annihilation.

That other German was Johann Georg Elser, (1903-1945), an artisan who had trained in carpentry and metalwork, become a cabinet-maker in 1922, and worked in clock factories through the twenties. In 1928 he had joined a communist-led trade union as well as a front organisation called the RFK. He had been uninterested in ideological matters, however, attending a few meetings and spending more of his time flirting and playing music with a patriotic dance band. After Hitler’s ascent to the chancellorship in 1933, Elser’s political contacts ceased altogether, and in 1936, some months after the annexation of Austria and just before the Munich conference, this unknown man made the remarkable decision to assassinate Hitler. His resolve stiffened after the vivisection of Czechoslovakia he knew that the Nazis were driving Europe towards war.

Working alone, Elser, began stealing explosives from his factory. Learning that Hitler was due to address the Nazi Old Guard on November 8, in a Munich beer hall and restaurant called the Burgerbraukeller, he attended the occasion and observed the Fuhrer’s movements. He then decided to plant a time-bomb in a pillar near the speaker’s rostrum. In March 1938, shortly after the Nazis annexed what remained of Czechoslovakia, Elser resigned his job and returned to Munich with his life savings of 400 marks. He acquainted himself with the beerhall, and then took up residence at his parental home in the town of Konigsbronn. Confiding only in his father, he worked briefly in a stone quarry, augmenting both his knowledge and stock of explosives.

On August 5 1939, Johann Georg began implementing his plan. Each night he would eat dinner in the beerhall, hide himself in a storeroom till it closed, and then emerge to work for some hours on the stone pillar inside which he was intending to plant his bomb. He worked like this for over thirty days, constructing a hollow space of 80 square centimeters with a small hinged door, neatly fitted to avoid detection. The space was lined with tin to prevent accidental damage caused by a nail and with cork, to muffle the sound of the clocks, of which two were planted to make doubly sure the device did not fall. He would carry all the rubble out in his hands every night, and because he was working on his knees, they soon became septic. On Monday, November 6 1939 he set the mechanism to explode at 9:20 pm on Wednesday the 8th. Down to his last ten marks he took 30 marks from his sister in Stuttgart, and then proceeded to Constance on the Swiss border.

Hitler appeared on Wednesday, but cut short his speech to less than an hour, ending it before 9:10 pm, and leaving immediately thereafter. The bomb exploded at 9:20 killing a waitress and six members of the Nazi party. A gap of less than ten minutes had intervened to save Hitler.

Elser was examined by customs officials at the Swiss frontier, and was found carrying a picture postcard of the Burgerbraukeller, notes on munitions factories, and his old RFK membership card. This was his one mistake, motivated perhaps, by sentiment. It was to cost him his life. He was detained on suspicion of being a spy and sent to Munich. Meanwhile the Gestapo had launched a manhunt for the unknown bomber. On November 13, after learning that the device had been planted at floor level, the head of the Gestapo’s investigation commissions asked to see Elser’s knees. He confessed after fourteen hours of interrogation.

Hitler himself, and Himmler, the head of the Gestapo, refused to believe the confession. On the 9th two British secret agents had been arrested near the Dutch border, and the Nazis were keen to use the bomb episode anti-British war propaganda. Moreover, it was politically damaging for them to admit that a German worker had planned and executed such a coup. Elser was subjected to another prolonged interrogation in Berlin, by which time his family had been rounded up. Despite brutal torture, he refused to doctor the truth, which was that he had acted alone, or to implicate anyone else. He was kept alive in order to give credence to a British plot to be fabricated in a trial the Nazis planned to hold after their victory. When defeat started them in the face, he was shot on April 9, 1945.

In Elser’s presence, reported the Gestapo, “One completely forgot that one was in the presence of a satanic monster”. Coming from such a source, that comment is testimony to the ordinariness of this man, of whom the Czech litterateur J.P. Stern wrote, that to find Hitler’s true antagonist, “We must look for a Nobody like himself, one who, sharing his social experiences yet lived and died on the other side of the moral fence.” (We must thank this professor for being perhaps the sole writer to give Elser his due place in the historical record.) He had the stubbornness to refuse salute the swastika, and to leave rooms whenever Hitler’s speeches were being broadcast, yet his motivations remained unintellectual – for him, doing something meant to do something with his hands. Johann Georg did break down under torture, saying that if his plan had not succeeded, it was because it was not meant to succeed. May we blame a man in his desperate position for trying to survive? We also learn from the archive that he had begun attending church during the months prior to November 1939. He had prayed in order to feel more composed and had convinced himself that he would go to heaven “If I have had the chance to prove by my further life that I intended good. By my deed I wanted to prevent even worse bloodshed.”

Featured Image Credits: Left – NPR and Right – Wikimedia Commons