Breaking epistemic barriers: Tribal ways of knowing and being

The discourse surrounding knowledge production in Indian academia has been profoundly influenced by colonial frameworks, which have historically positioned tribal communities as passive subjects rather than as active agents of knowledge production. Much of the existing scholarship concerning these communities continues to rely on texts authored by colonial ethnographers, whose observations were filtered through an epistemology of ‘othering.’ Such scholarship often depicted tribal societies as static, primitive, and isolated from so-called mainstream civilization. This approach not only distorted tribal lived realities but also contributed to the systemic marginalisation of their intellectual traditions. Consequently, to decolonise Indian academia, it is imperative to recognize and engage meaningfully with tribal epistemologies and ontologies, acknowledging their ways of knowing and being as integral to the broader intellectual landscape. It is crucial to acknowledge that much of the prevailing “knowledge” about tribes in academic and other supposedly “scientific” and credible domains was, in reality, a product of colonialism and coloniality, presented under the guise of scientific inquiry and modernity. [1]

This exposition critically examines the persistence of colonial epistemologies in Indian academic discourse, particularly about Janjatiya communities. It highlights how tribal knowledge systems, oral traditions, and ontological perspectives have been systematically excluded, calling for a shift towards decolonial methodologies that recognise and validate tribal intellectual traditions.

Colonial Legacy in knowledge production

The colonial ethnographic tradition entrenched a hierarchical mode of knowledge production that positioned European epistemologies as superior, relegating tribal knowledge systems to the periphery. British administrators and scholars, though instrumental in documenting linguistic, cultural, and social practices of various tribal groups, nonetheless perpetuated an external, extractive, and hierarchical gaze. Their studies were largely undertaken with the objective of governance and control rather than a genuine engagement with tribal ontologies. As a result, the academic discourse surrounding tribal communities was often filtered through reductionist lenses, reinforcing stereotypes and contributing to their exclusion from dominant knowledge structures.

H.H. Risley’s racial classification

British administrator and ethnographer H.H. Risley classified Indian communities, including tribal groups, by measuring nasal indices to categorize them into hierarchical racial groups. His work, such as The Tribes and Castes of Bengal (1891), framed tribes as “primitive” and racially distinct from caste Hindus, reinforcing notions of racial superiority and justifying colonial rule. [2]

Verrier Elwin’s romanticization

While Elwin’s work, such as The Baiga (1939) and The Muria and Their Ghotul (1947), documented tribal life in central India, his portrayal of tribal communities as isolated, mystical, and in need of protection from modernity often overlooked their dynamic interactions with the broader socio-political landscape. His perspectives influenced Indian policy, leading to paternalistic approaches that viewed tribes as subjects to be preserved rather than as active participants in shaping their futures. [3]

Denial of tribal environmental knowledge

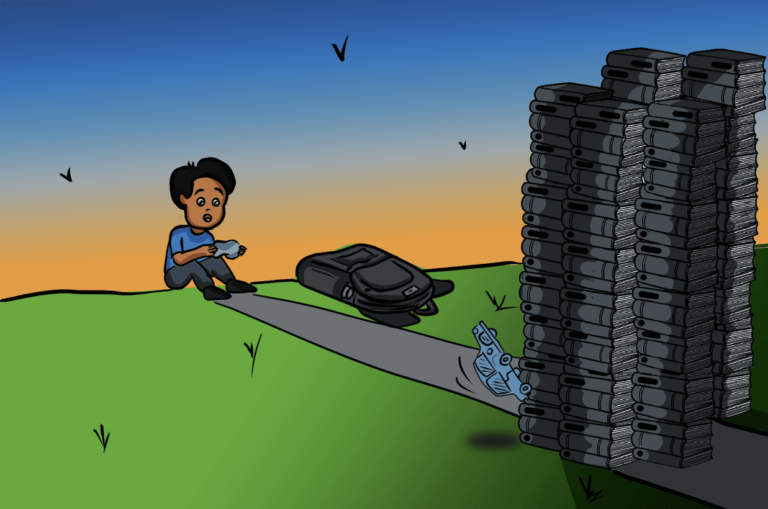

Colonial forestry policies dismissed tribal ecological knowledge in Favour of exploitative resource management practices. For example, the shifting cultivation methods of the Dondria Kondh and the agroforestry traditions of the Gond community were labelled as “primitive” and “unscientific,” leading to displacement and restrictions on their traditional land-use practices. The use of Western anthropological categories continues to shape policies, sometimes reinforcing rigid categorizations that fail to capture the complexities of tribal identities and their socio-political realities. The term “primitive” continues to be employed uncritically within Indian academic discourse, often without rigorous introspection or engagement with its colonial and pejorative connotations. This is evident in scholarly works such as a 2011 publication on the Dondria Kondh tribe of Odisha, which perpetuates this terminology, reinforcing outdated and hierarchical narratives about tribal communities. Such usage reflects the enduring impact of colonial epistemologies that frame tribal societies as static and underdeveloped, rather than recognizing their dynamic cultural systems and knowledge traditions.

Even in the post-colonial era, this bequest has endured, as Western positivist methodologies—with their emphasis on objectivity, empirical validation, and textual authority—continue to shape research and pedagogy. Such methods often fail to account for the nuanced, oral, and performative dimensions of tribal epistemologies, thus rendering them invisible within dominant academic discourse. By continuing to privilege these approaches, academia perpetuates epistemic violence against tribal knowledge systems, reinforcing historical structures of exclusion.

Post-colonial academia continued to privilege textual sources over oral traditions. For instance, the Jingrwai Iawbei (song sung in honour of the root ancestress) of the Khasi community, particularly practiced in Kongthong village, East Khasi Hills district, Meghalaya, serves as a vital cultural and epistemic marker of Khasi matrilineal society. [4] These songs encapsulate ancestral lineage, social identity, and tribal knowledge systems, offering a rich oral historiography that has sustained across generations. Gond art from Madhya Pradesh visually represents the community’s cultural traditions, spirituality, and connection with nature. Created during festivals like Karwa Chauth, Diwali, Ashtami, and Nag Panchami, it draws from mythology, folklore, and daily life, depicting emotions, dreams, and tribal knowledge. [5] The Warli painting is distinguished by its symbolic storytelling and geometric simplicity, reflecting the tribe’s deep connection to nature. Circles represent celestial bodies, triangles signify mountains and trees, and squares denote human settlements. In Gujarat, Warli art extends beyond decoration, capturing daily life, rituals, and ecological harmony. It serves as a medium of storytelling, reinforcing community identity and spiritual beliefs, especially during festivals and significant events. [6]

However, mainstream historiography has frequently overlooked these oral traditions, privileging colonial archival materials instead. This continued reliance on colonial documentation marginalises tribal epistemologies and reinforces the erasure of tribal modes of knowledge transmission from academic discourse. Tribal oral traditions, which encapsulate historical memory, spiritual knowledge, and socio-cultural values, have often been relegated to the realm of folklore or entertainment rather than being recognised as legitimate sources of history and philosophy.

Colonial and postcolonial academic discourses have frequently exoticised these traditions through an orientalist lens, framing them as artefacts of a “primitive” past rather than dynamic knowledge systems embedded in contemporary tribal societies. By divorcing these traditions from their spiritual and socio-cultural contexts, scholars have often reduced them to performative spectacles, neglecting their deeper significance as repositories of ethical codes, ecological wisdom, and community governance.

Need for an epistemological shift

Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge, dictates which forms of knowing are considered valid and whose perspectives are given legitimacy within academic institutions. In the case of Janjatiya communities, their tribal knowledge traditions—rooted in oral histories, ecological wisdom, and relational ways of knowing—have been systematically marginalized. The dominant knowledge paradigms in Indian academia have largely ignored the epistemic validity of these traditions, reinforcing a monolithic intellectual framework that fails to reflect the diversity of knowledge systems present in India.

A decolonized epistemology would necessitate an active engagement with tribal ways of knowing. Decoloniality is both an analytical and practical framework aimed at challenging and dismantling the enduring legacies of colonialism and imperialism across various fields, including education. It seeks to shift the focus away from Eurocentric perspectives by recognizing, privileging, and legitimizing Indigenous, non-Western, and subaltern knowledge systems and worldviews. [7-8]

Decoloniality actively confronts epistemicide—the systematic silencing and erasure of diverse knowledge traditions—perpetuated by Eurocentric and colonial frameworks of understanding. [9-10] Within academia, decoloniality holds significant value as a transformative approach that enables the reassessment, reconstruction, and revalidation of marginalized knowledge systems and pedagogies. For example, the Gond community’s pictorial storytelling serves as an epistemic framework through which they interpret and pass down historical, ecological, and spiritual knowledge. Such traditions challenge the hegemony of written text-based knowledge systems and call for an expansion of the academic canon to include alternative forms of knowledge transmission.

A meaningful epistemological shift also necessitates methodological innovations. Collaborative ethnography, participatory research, and tribal storytelling methodologies can serve as effective tools to bridge the gap between academia and tribal communities. By centering tribal voices and moving beyond extractive research models, scholars can co-create knowledge that is more representative and ethically responsible.

Ontology and tribal ways of Being

Ontology, the philosophical study of being, is deeply intertwined with epistemological concerns. Western ontologies, largely shaped by Cartesian dualism, have traditionally emphasized separation—between humans and nature, subject and object, and mind and body. Such ontological perspectives have informed colonial knowledge production, which often viewed tribal communities as primitive and pre-modern, reinforcing artificial distinctions between different groups.

In contrast, tribal ontologies frequently emphasize interconnectedness, relationality, and reciprocity. The Santhal, Khasi and Bhil communities, for instance, hold belief systems that conceptualize nature not as a resource to be exploited but as a sentient entity with which humans share reciprocal obligations. Such ontological perspectives challenge the exploitative logic of colonial capitalism, which sought to commodify land, labor, and resources in ways that disrupted tribal modes of existence.

Incorporating tribal ontologies into academic discourse requires a radical rethinking of existing disciplinary boundaries. Integrating tribal environmental philosophies into sustainability studies, for instance, can provide more holistic approaches to ecological conservation. Similarly, recognizing tribal healing practices within medical anthropology can challenge biomedical hegemonies and foster a more pluralistic understanding of health and well-being.

Integrating tribal ontologies requires not just recognition but a fundamental shift in academic methodologies. Moving beyond token acknowledgement, academia must adopt participatory, community-centered approaches that position tribal communities as co-producers of knowledge. Decolonizing methodologies and academic practices thus become essential in challenging and transforming existing knowledge paradigms.

Decolonizing methodologies and academic practices

The project of decolonizing academia extends beyond theoretical critique; it necessitates tangible shifts in academic practice and institutional structures. Some critical interventions include:

- Integrating Tribal Knowledge Systems in Curricula: Universities must actively incorporate tribal epistemologies within their syllabi, ensuring that students are exposed to diverse intellectual traditions beyond Eurocentric theories.

- Adopting Decolonized Research Methodologies: Scholars should move beyond extractive research practices and embrace participatory, community-led models that recognize Janjatiya communities as active knowledge producers rather than passive subjects.

- Language Accessibility and Knowledge Dissemination: Much of academic knowledge remains inaccessible to the communities it seeks to represent. Decolonizing academia also entails making research findings available in tribal languages and using non-textual modes of dissemination, such as visual storytelling and oral narratives.

- Recognizing Oral Traditions and Non-Textual Knowledge: A decolonized academic framework must validate oral histories, tribal performances, and non-written sources of knowledge as legitimate epistemic contributions.

Conclusion

The process of decolonizing Indian academia requires a conscious dismantling of the colonial intellectual legacy that continues to shape knowledge production. Engaging with tribal epistemologies and ontologies not only addresses historical exclusions but also enriches academic discourse by incorporating diverse ways of knowing and being. By recognizing tribal communities as co-producers of knowledge, rather than mere subjects of study, academia can foster a more inclusive, ethical, and pluralistic intellectual landscape. Decolonization, therefore, is not merely an academic imperative but a necessary step toward epistemic justice and intellectual sovereignty.

References

- Bodhi, S. R (2022). Tribal Studies in India: Pre and Post-Xaxa. Journal of Tribal Intellectual Collective India. Vol.6 (1), TN (1), ISSN: 2321-5437 https://www.ticijournals.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Tribal-Studies-in-India-Pre-and-Post-Xaxa-1.pdf

- Risley, Herbert (1891). The Tribes and Castes of Bengal. Harvard Library: Bengal Secretariat Press.

- Elwin, Verrier (1939). The Baiga. The University of Michigan | Elwin, Verrier (1947). The Muria and Their Ghotul. Oxford University Press, London

- Dutta, Piyashi (2017). The Whistling Village. Economic and Political Weekly. Postscript Vol. 52, Issue No. 2, https://www.epw.in/journal/2017/2/postscript/%E2%80%8B-whistling-village.html

- Thamanna, Aiswarya and R. Subramani (2023). Indigenous Communication of Everyday Life and Philosophy: An Analysis of Gond Paintings in Madhya Pradesh. ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts. https://www.granthaalayahpublication.org/Arts-Journal/ShodhKosh/article/view/645/683

- (2024). The Tribal Art of Gujarat: Warli Painting. Hastkala Setu. Retrieved Feb 27, 2025 from https://hastkala.gujarat.gov.in/blogs/public/details/the-tribal-art-of-gujarat:-warli-painting

- Mignolo, W. D. 2011. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2013. “Why Decoloniality in the 21st Century?” The Thinker 48: 10–15. https://hdl.handle.net/10210/470999(open in a new window).

- Quijano, A. 2000. “Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America.” International Sociology 15 (2): 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580900015002005.

- Grosfoguel, R. 2013. “The Structure of Knowledge in Westernised Universities: Epistemic Racism/Sexism and the Four Genocides/Epistemicides of the Long 16th Century.” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge 1 (1): 73–90.