A visit to ‘Om shree panch pir samadhi sthal’

The entrance

Lying just next to the famous Taj Mansingh Hotel in Central Delhi, is a small obscure shrine which is known as ‘Om Shree Panch Pir Samadhi Sthal’. The shrine is bound by a thick brick wall leaving only a small entrance to the front. Within its boundaries exists a tree under which one can find many modern sculptures of popular Hindu deities such as that Shiva, Krishna, and Durga and along with them some interesting remains of an early-medieval Jain figurine, which with some skepticism can be identified as that of goddess Ambika.

However, what’s particularly unique about this shrine is the five graves lying on an upraised platform under a tin shed. These graves are identified as ‘samadhi’ of Panch Pirs, namely of Baba Karam Nath, Baba Dharm Nath, Baba Shyam Nath, Baba Ram Nath and the one which has a statue dedicated to him just atop his ‘samadhi’ is of Baba Shankar Nath.

As per the current priest Satguru Shivlal Maharaj of the shrine, who identifies himself as a Brahmin from Uttar Pradesh, this shrine belongs to the period of the Mughal ruler Aurangzeb. The Pirs were brothers and were famous for their miracles and hence, attracted adulation from the local populace constituting of both Hindus and Muslims, and it’s at this place where their ‘samadhi’ exists. Nothing more appears to be known of these pirs.

While the authenticity of the existence of such pirs in the past cannot be attested as of now, this shrine in Delhi appears to be a manifestation of the cult of ‘Panch Pir’ (which can be translated as ‘five saints’).

The cult of Panch Pirs

These cults were extremely popular across the Indian subcontinent from the medieval to the early modern period. The term ‘Panch’ or five has been seen as related to the five Dhyani Buddhas, the Pandavas, to even Muhammad and his four companions (Char Yar). It seems that the number five was chosen for its diverse cultural formulation across various geographies. In any case, the number five is better than one when seen in the context of a largely non-monotheistic population that these cults wanted to lure.

The saints more often than not were sufis, whose composition varied from region to region. These saints were collectively subject to popular myth-making and were attached to various mystical-magical powers which attracted a large following. In the regions of Punjab, the cult of Panch Pirs came to include the five famous saints of the Chisti Sufi order, including within them the famous saint Muin ud-Din Chisti. In Bengal, these saints included Pir Badr, Gazi Mian, Khawaza Khizr along with others. While in the Mewar region of Rajasthan, the saints included within the Panch Pirs were namely Pabuji, Harbuji, Ramdevji, Goga Ji, and Meha Ji. It’s interesting to note that the individual cult of Ramdevji and Goga Ji is still popular across North India.

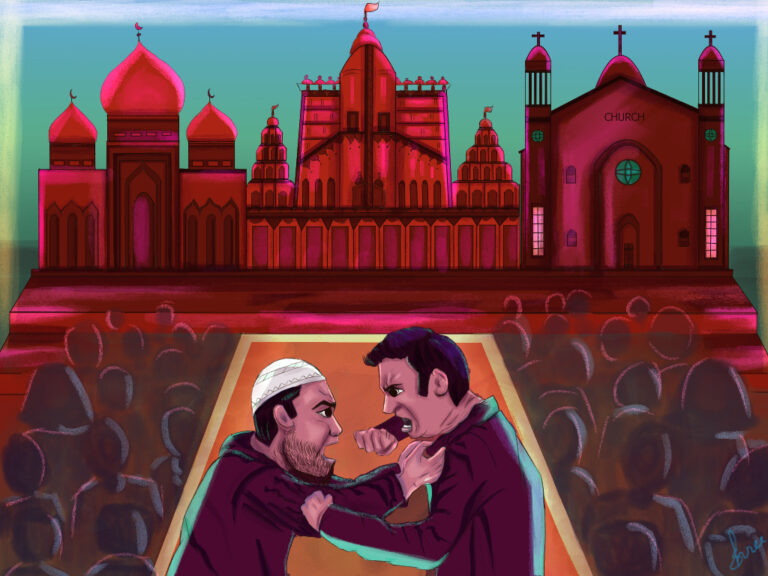

What’s interesting about these cults is that they not only attracted worship from Muslims but also from non-Muslims, particularly of the lower castes. These cults in one way or another involved the introduction of Islamic elements, whether it is grave worship or the larger Islamic theological elements, in a non-Islamic setting through appropriation, interpretation, and re-interpretation of local cultural elements.

For instance, in Bengal these Pirs were said to have control over various facets of nature, controlling from storms to rain, and were often represented through the appropriation of local symbols, Gazi Mian is represented as riding a tiger, while Khwaza Khizr who is said to be residing in rivers and seas is said to ride a fish as his vahana. Even the legends of Ramdevji and Gogaji have distinct Islamic influences.

The appearance of these cults has been interpreted along various lines, popular among them is to see these cults as representative of Hindu-Muslim syncretism. However, such an interpretation involves not just imposition of the present day essentialized notions of ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ on a back date, when religious identities were in flux and in the process of formation, but such a conception also fails to explain as of why such cults emerged and what purpose they served.

Richard Eaton has identified various stages of Islaminisation in the context of Bengal, the first stage involves the ‘inclusion’ of Islamic elements in a local tradition, the second stage involves the ‘identification’ of specific Islamic figures with that of local traditions, and the last stage involves ‘displacement’ of local traditions. The last stage leads to the creation of a more homogenized Islamic tradition as guided by the Islamic literary culture through the active elimination of local non-Islamic elements. This formulation of Eaton can be used to understand the phenomenon of the prevalence of the cults of Panch Pirs, which served the purpose of facilitating the gradual Islaminisation of the local population.

The Case of ‘Om Shree Panch Pir Samadhi Sthal’

The case of ‘Om Shree Panch Pir Samadhi Sthal’ of Delhi is unique in the sense that it appears to have escaped a full-fledged ‘Islaminisation’, instead, the cult went through a process of ‘Hindunization’ in recent times. A report in the Times of India, titled as ‘Temple encroaches on bungalow’ from February 24, 2010, registered a complaint by the officials against encroachment on public land by ‘Om Shree Panch Pir’ temple, it goes on to state that as per the officials the place use to be an old ‘mazar’.

From this, we can infer two things, either the ‘Hindunization’ of the shrine from being identified as a mazar to a temple/samadhi is a recent phenomenon or the officials failed to understand the complexities of religious traditions and wrongly identified any shrine housing graves as a mazar. Whatever the case, the present shrine of ‘Om Shree Panch Pir Samadhi Sthal’ assertively displays its Hinduness.

Though retaining the identification of the saints as ‘pir’, the graves have come to be seen as ‘samadhi sthal’ by the locals and the worshippers, who are largely Hindus, though the chief priest claims that the shrine attracts people from across religions. Adding to the ‘Hinduness’ of this shrine, the names of the pirs have been standardized in Sanskrit, sculpture of pirs and other popular Hindu gods have been incorporated within the shrine. And obviously, the very epithet ‘Om Shri’ to the Panch Pirs proudly displays their Hindu character.

The reason for such a transformation of the character of the shrine, at best, should be left for more thorough future research. However, some general comments can be made. This transformation of the shrine can be attributed to the nature of postcolonial societies, where communities tend to define their religious identities in an exclusivist sense. The changing character of the shrine of ‘Om Shree Panch Pir Samadhi Sthal’ can be said to showcase such a phenomenon.

References

- Eaton, R. M., & Eaton, R. M. (1993). The rise of Islam and the Bengal frontier, 1204-1760 (Vol. 17). Univ of California Press.

- Roy, A. (2014). The Islamic syncretistic tradition in Bengal. In The Islamic Syncretistic Tradition in Bengal. Princeton University Press.

- Rahman, M. S. N. (1989, January). PIR CULT AS EVIDENCE OF HINDU-MUSLIM AMITY IN MUGHAL BENGAL. In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress (Vol. 50, pp. 280-283). Indian History Congress.